Germany’s invasion of Ukraine in 1941 led to the total destruction of the Jewish households in Izyaslav. Now only 9 Jews reside in Izyaslav but in 1939, before the war, about one third of Izyaslav’s population, 3200 people, was Jewish. Jews arrived in Izyaslav in the first half of the 16th century, and by 1897 half of Izyaslav’s residents, six thousand, were Jews.

The Germans captured Izyaslav on July 5, 1941, and it didn't take long for the mass executions to start. A few local Jews managed to escape to the Soviet interior when the Germans arrived, while the remaining Jews were ordered to wear yellow badges on their chests and backs. On August 30, 1941 the local police and the Germans surrounded the city and ordered the Jews to gather for the “resettlement in Palestine”.

On that day, more than 1000 Jews were murdered in Poboy antitank caponiers on the western outskirts of town.

Even larger mass killings would be carried out 10 months later in the Soshne forest, where the new commemorative monument will reside.

After the first killing operation, a ghetto comprising about 20 houses was set up near the Old Synagogue building in the old city and the remaining Jews of Izyaslav and nearby localities were brought there. The ghetto was surrounded with barbed wire and a wooden fence and guarded by the local police. The Jews stuck there were used for hard labor and not allowed to leave. Many of them died during the construction of the dam on the Gorin river and were buried inside it. But over 2,000 of the Jews in this ghetto were killed in the Soshne forest.

The Germans captured Izyaslav on July 5, 1941, and it didn't take long for the mass executions to start. A few local Jews managed to escape to the Soviet interior when the Germans arrived, while the remaining Jews were ordered to wear yellow badges on their chests and backs. On August 30, 1941 the local police and the Germans surrounded the city and ordered the Jews to gather for the “resettlement in Palestine”.

On that day, more than 1000 Jews were murdered in Poboy antitank caponiers on the western outskirts of town.

Even larger mass killings would be carried out 10 months later in the Soshne forest, where the new commemorative monument will reside.

After the first killing operation, a ghetto comprising about 20 houses was set up near the Old Synagogue building in the old city and the remaining Jews of Izyaslav and nearby localities were brought there. The ghetto was surrounded with barbed wire and a wooden fence and guarded by the local police. The Jews stuck there were used for hard labor and not allowed to leave. Many of them died during the construction of the dam on the Gorin river and were buried inside it. But over 2,000 of the Jews in this ghetto were killed in the Soshne forest.

Records from the Yad Vashem Holocaust Center contain an account of these tragic events:

“In June 1942, Ukrainian auxiliary policemen surrounded the ghetto and ordered its inmates to come out of their homes. 137 specialists – artisans and craftsmen, with their families – were allowed to remain in the ghetto. The rest of the Jews were loaded onto trucks and taken to the forest near the village of Soshne, several kilometers west of the town. There they were shot to death in several large pits by a German unit and some Ukrainian policemen. On January 1, 1943 the artisans and craftsmen who had been held in one building were surrounded by Germans and Ukrainian policemen. Those who tried to run away were shot to death on the spot. The others were taken by truck to the same site and shot to death with sub-machine guns.”

“In June 1942, Ukrainian auxiliary policemen surrounded the ghetto and ordered its inmates to come out of their homes. 137 specialists – artisans and craftsmen, with their families – were allowed to remain in the ghetto. The rest of the Jews were loaded onto trucks and taken to the forest near the village of Soshne, several kilometers west of the town. There they were shot to death in several large pits by a German unit and some Ukrainian policemen. On January 1, 1943 the artisans and craftsmen who had been held in one building were surrounded by Germans and Ukrainian policemen. Those who tried to run away were shot to death on the spot. The others were taken by truck to the same site and shot to death with sub-machine guns.”

|

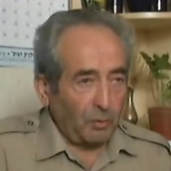

Semen Shider, a survivor of the Izyaslav ghetto liquidation, described the horror: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=23&v=SoQ0KKgN3CM |

Another witness of the executions in Izyaslav wrote a passionate letter to his uncle Misha:

“Hello, Uncle Misha!

I am writing from my home town of Izyaslav, which you wouldn’t longer recognize. Only the miserable half of our village remains. But why was it left there at all? It would have been better for it never to have existed, better for me had I not been born into the world! I am no longer the Syunka you once knew. I no longer know who I am myself. It all seems like a dream, a nightmarish dream. Out of eight thousand people in Izyaslav, only our

neighbor Kiva Feldman and I are left. My dear Mama and Papa, my sweet brother Zyama, Iza, Sarra, Borukh — all of them are gone. You sweet, dear people, how very hard it was for you! I cannot come to my senses, I cannot write. If I were to begin to tell you what I have lived through, I do not know how you could comprehend it.

Three times I broke out of a concentration camp; more than once I have looked death in the eye while fighting in the ranks of the partisans.

I am now beginning a new life — the life of an orphan. How? I myself do not know. Write as often as possible; I await your reply. Why don't Uncle Shloime, Iosif, Gitya, and the others write?

With warm greetings,

Your nephew Syunya Deresh

14 March 1944”

“Hello, Uncle Misha!

I am writing from my home town of Izyaslav, which you wouldn’t longer recognize. Only the miserable half of our village remains. But why was it left there at all? It would have been better for it never to have existed, better for me had I not been born into the world! I am no longer the Syunka you once knew. I no longer know who I am myself. It all seems like a dream, a nightmarish dream. Out of eight thousand people in Izyaslav, only our

neighbor Kiva Feldman and I are left. My dear Mama and Papa, my sweet brother Zyama, Iza, Sarra, Borukh — all of them are gone. You sweet, dear people, how very hard it was for you! I cannot come to my senses, I cannot write. If I were to begin to tell you what I have lived through, I do not know how you could comprehend it.

Three times I broke out of a concentration camp; more than once I have looked death in the eye while fighting in the ranks of the partisans.

I am now beginning a new life — the life of an orphan. How? I myself do not know. Write as often as possible; I await your reply. Why don't Uncle Shloime, Iosif, Gitya, and the others write?

With warm greetings,

Your nephew Syunya Deresh

14 March 1944”

The uncle, Michael I. Eisenberg, received the letter in 1944 serving in Soviet Army fighting Nazi. Eisenberg sent this letter to well-known Soviet writer Ilya Ehrenburg, which included Deresh’s letter published in his famous “Black Book”, a collection of testimonies, letters, diaries and other documents on Nazi anti-Jewish activities in Eastern Europe. Click on the following link to see a live reading of Deresh’s letter:

https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/tkfgen/arch/audio/A_letter_to_Uncle_Misha.mp4

https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/tkfgen/arch/audio/A_letter_to_Uncle_Misha.mp4

|

The Soshne killing site contains two commemorative sculptures telling the story of one family torn apart by the murders at Izyaslav. The sculpture of a girl commemorates the short life of Svetlana Korosty (Коростий), who was born on March 31, 1938 and killed by policemen in September 1943. The other sculpture is of her father Saveliy Pavlovich Korosty, who was a teacher in Izyaslav’s school in the 1930s and became a tank commander shortly before the war.

Sveta’s Jewish mother Rita Yakovlevna Goldshtein was a former student of Saveliy Korosty. The teacher and the student fell in love, got married and had Svetlana in 1938. In 1941, the Korostys brought Sveta to Izyaslav and left her in the care of Rita’s parents for the summer, as they had done in previous years. Tragically, the war started on June 22, 1941, and the German army quickly occupied Izyaslav and most of the Ukraine, separating Sveta from her parents. Both parents survived the war, with Savely Korosty earning command of the 1825 Тank Regiment, and later becoming а general. After the war, the Korostys came to Izyaslav to take their daughter back and learned of the shocking death of Svetlana and her Jewish grandparents. The Korostys were devastated. Sveta’s father requested that he be buried near his daughter and asked for the following words to be on his monument: “I come to you my dear daughter...” (Я прийшое до тебе люба донні...) |

The pain and suffering of millions of Holocaust victims should be acknowledged by future generations:

“We live – in the mundanity we live,

And memories we’re wrapping in the cape –

The sound of lamenting to escape...

We dream of the lament, it beckons – beckons in the dream...”

From «Krasnostav Requiem» by Ilya Shifrin English translation by Irina Barskova

“We live – in the mundanity we live,

And memories we’re wrapping in the cape –

The sound of lamenting to escape...

We dream of the lament, it beckons – beckons in the dream...”

From «Krasnostav Requiem» by Ilya Shifrin English translation by Irina Barskova

TKF is working to locate the descendents of Izyaslav residents Mariya Finkel (née Yakubovskaya), Mikhail Kropovenskiy, and Yevgenia Sveshnikova; we would like to invite them to the Opening of the Holocaust Monument at Soshne forest. Those three Izyaslav residents rescued Sofya Finkel during the Holocaust and were recognized by Yad Vashem in 1995 as Righteous Among the Nations. The story of Sofya’s rescue is below:

On September 9, 1942, in the last Aktion, the Germans liquidated most of the town’s remaining Jews, among them Salomon Finkel and his family. His 14-year-old daughter Sofya was the only family member who escaped from the death pits in Soshne forest.

She fled to her aunt Mariya, who welcomed the child into her house and hid her from the neighbors for several weeks. Since Finkel’s house was not a safe haven for her niece, she moved Sofya to the nearby home of the Kropovenskiy family, where Mikhail Kropovenskiy lived with his married sister Yevgeniya Sveshnikova and her infant son.

From late 1942 until autumn 1943, the Jewish girl hid alternately in their attic, cellar, and granary; once in a while she was even able to visit Mariya Finkel for short periods. In September 1943, Kropovenskiy contacted Soviet partisans, who allowed him and Sofya to join the Mozolev partisan unit in the forest; they stayed with the unit until the liberation of the area in March 1944. After the war, Sofya settled in the neighboring town

of Shepetovka and kept in touch with her rescuers. Sofya died in 2010, leaving no family behind.

On September 9, 1942, in the last Aktion, the Germans liquidated most of the town’s remaining Jews, among them Salomon Finkel and his family. His 14-year-old daughter Sofya was the only family member who escaped from the death pits in Soshne forest.

She fled to her aunt Mariya, who welcomed the child into her house and hid her from the neighbors for several weeks. Since Finkel’s house was not a safe haven for her niece, she moved Sofya to the nearby home of the Kropovenskiy family, where Mikhail Kropovenskiy lived with his married sister Yevgeniya Sveshnikova and her infant son.

From late 1942 until autumn 1943, the Jewish girl hid alternately in their attic, cellar, and granary; once in a while she was even able to visit Mariya Finkel for short periods. In September 1943, Kropovenskiy contacted Soviet partisans, who allowed him and Sofya to join the Mozolev partisan unit in the forest; they stayed with the unit until the liberation of the area in March 1944. After the war, Sofya settled in the neighboring town

of Shepetovka and kept in touch with her rescuers. Sofya died in 2010, leaving no family behind.

|

Intereview with Sofya Finkel https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dIQs-S4wInk Sofya (Sofia) Finkel, who was born in Izyaslav, Ukraine in 1927 and was living there during the war years, testifies about the killing of Jews during the liquidation of the town's ghetto in the summer of 1942. She retells the story as she heard it, while hidden, from a Ukrainian auxiliary policeman who had participated in the murders. |