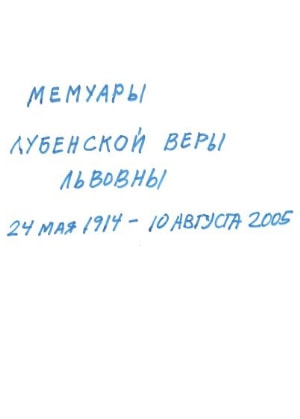

Lubensky memoirs

From pogroms to Holocaust.

...........

I witnessed and was lucky to survive horrific Jewish pogroms in Chigirin in 1919.

It all started like that. At the time of my story, our family resided at my grandfather’s house in Matveevka. The family owned a small store.

One day quite late in the evening we saw a cart carrying 4 – 6 men stop at the entrance to our house.

I witnessed and was lucky to survive horrific Jewish pogroms in Chigirin in 1919.

It all started like that. At the time of my story, our family resided at my grandfather’s house in Matveevka. The family owned a small store.

One day quite late in the evening we saw a cart carrying 4 – 6 men stop at the entrance to our house.