Communities > about a shtetl

About a Shtetl

|

Alexander Pavlenko, Germany: Everyday life in Jewish Shtetl at the beginning of the 20th century. Variations on subjects of Sholem Aleichem, Marc Chagall, Solomon Yudovin.

|

The life structure was similar in most shtetls. The life of the Jew oscillated between synagogue, home and market. In the synagogue he served God, studied His Law and participated in social activities. The traditional ideals of piety, learning and scholarship, communal justice, and charity, were fused in the intimate lifestyle of the shtetl.

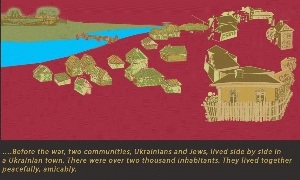

However, history, locality, size, level of prosperity and other nuances create variety and distinction between them. The Yiddish term for town, shtetl commonly refers to small market towns in pre–World War II Eastern Europe with a large Yiddish-speaking Jewish population. While there were in fact great variations among these towns, a shtetl connoted a type of Jewish settlement marked by a compact Jewish population distinguished from their mostly gentile peasant neighbors by religion, occupation, language, and culture.

|

The shtetl was defined by interlocking networks of economic and social relationships: the interaction of Jews and peasants in the market, the coming together of Jews for essential communal and religious functions, and, in more recent times, the increasingly vital relationship between the shtetl and its emigrants abroad.

Samuel Kassow, noted historian, offers the following definition of a shtetl:

“In defining a shtetl, the following clumsy rule probably holds true: a shtetl was big enough to support the basic network of institutions that was essential to Jewish communal life—at least one synagogue, a mikveh [a ritual 6 samuel kassow bath], a cemetery, schools, and a framework of voluntary associations that performed basic religious and communal functions. This was a key difference between the shtetl and even smaller villages, and the perceived cultural gap between shtetl Jews and village Jews (yishuvniks) was a prominent staple of folk humor. On the other hand, what made a shtetl different from a provincial city was that the shtetl was a face-to-face community. It was small enough for almost everyone to be known by name and nickname. Nicknames could be brutal and perpetuated a system that one observer called the “power of the shtetl” to assign everyone a role and a place in the communal universe.”

“In defining a shtetl, the following clumsy rule probably holds true: a shtetl was big enough to support the basic network of institutions that was essential to Jewish communal life—at least one synagogue, a mikveh [a ritual 6 samuel kassow bath], a cemetery, schools, and a framework of voluntary associations that performed basic religious and communal functions. This was a key difference between the shtetl and even smaller villages, and the perceived cultural gap between shtetl Jews and village Jews (yishuvniks) was a prominent staple of folk humor. On the other hand, what made a shtetl different from a provincial city was that the shtetl was a face-to-face community. It was small enough for almost everyone to be known by name and nickname. Nicknames could be brutal and perpetuated a system that one observer called the “power of the shtetl” to assign everyone a role and a place in the communal universe.”

The shtetl pattern first took shape within Poland-Lithuania before the partition of the kingdom. Jews have been invited to settle in the private towns owned by the Polish nobility that developed from the 16th century, on relatively very favorable conditions. In many of such private towns Jews soon formed the preponderant majority of the population.

|

Originally dependent on the highly structured and powerful communities in the larger cities from which the settlers first came, these small communities increasingly acquired importance, since their development was unhampered by the established rights and inimical anti-Jewish traditions of the Christian towns-people, as the communities in the old “royal towns” had been. Thus the movement of Jews to smaller towns where they were needed, and therefore protected, by the greater and lesser Polish nobility, continued.

The shtetl was also marked by occupational diversity. |

While elsewhere in the Diaspora Jews often were found in a small number of occupations, frequently determined by political restrictions, in the shtetl Jewish occupations ran the gamut from wealthy contractors and entrepreneurs, to shopkeepers, carpenters, shoemakers, tailors, teamsters, and water carriers. This striking occupational diversity contributed to the vitality of shtetl society and to its cultural development. It also led to class conflict and to often painful social divisions.

References:

1. Samuel Kassow , “Shtetl”, The Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

2. Mark Kupovetsky, “Population and Migration before World War I”, The Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, YIVO Institute for Jewish

Research

3. Adam Teller, Economic Life, The Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

4. Mark Zborowski, “Shtetl”, Encyclopedia Judaica, Jewish Virtual Library, The Gale Group

2. Mark Kupovetsky, “Population and Migration before World War I”, The Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, YIVO Institute for Jewish

Research

3. Adam Teller, Economic Life, The Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

4. Mark Zborowski, “Shtetl”, Encyclopedia Judaica, Jewish Virtual Library, The Gale Group